CHI’s West Coast Summit on Health Equity 2025 w/ BeOne Medicines

Theme: The Importance of Access

Dates: 8 December, 2025

Location: 835 Industrial Rd 6th floor, San Carlos, CA 94070

WATCH THE FULL SUMMIT BELOW

In December 2025, BeOne Medicines partnered with the Center for Healthcare Innovation (CHI) to host a day-long West-Coast Summit on Health Equity in San Carlos, California. Scientists, clinicians, community leaders, health-equity advocates, and mental health providers came together around a shared tension that framed the entire conversation:

We live in a moment of extraordinary scientific and technological progress—yet the people who most need these advances still struggle to access them.

The summit functioned as both a mirror and a blueprint. It held up an honest reflection of how structural inequities, politics, and mistrust continue to shape health outcomes in the United States, and it also surfaced concrete strategies for doing things differently—at the level of clinical trials, community engagement, mental health, and technology design.

What follows is a narrative overview of what was discussed, the issues and barriers that emerged, and the solutions and possibilities that participants began to chart together.

The health-equity landscape: Little progress, rising headwinds

CHI Board Member and Panel Moderator, Lynn Hanessian opened with sobering context: despite decades of rhetoric and scattered initiatives, the United States has made very little real progress in advancing health equity. Racial and ethnic inequities remain embedded in how care is funded, organized, and delivered. These inequities are not peripheral flaws; they are structural features of the system.

Participants connected this stalled progress to a broader social and political climate. They named the looming impact of policies, increasing political polarization, widening economic divides, and a deep shift in trust in key institutions—from government and academia to public health and media.

Within that context, participant Lisa Delancy voiced a concern that resonated across the room: we appear to be moving away from a shared moral obligation to care for one another. The sense of solidarity that should underpin health systems has been gradually reframed as optional, private, or transactional.

Yet the conversation was not purely pessimistic. Participants also highlighted moments when focused public-health efforts have worked. In Chicago, recent measles outbreaks among newly arrived migrants triggered a coordinated, community-based response that quickly improved vaccination rates. That example, and others like it, served as proof that when incentives, communication, and community partnership line up, progress can happen quickly.

Trust in healthcare: Fragile, earned, and rational

Again and again, the discussion returned to trust as the rate-limiting factor for equitable care and research.

Capt. Julius Pryor III, speaking from his experience at BeOne Medicines, named the central paradox: we have world-class medical technologies, but people who most need them either cannot access them—or do not trust the systems offering them. Trust deficits, participants emphasized, are not irrational; they are grounded in lived experience.

Historical abuses such as Tuskegee are only the most well-known examples in a longer pattern. Many communities have encountered health systems as sites of neglect, dismissal, or surveillance.

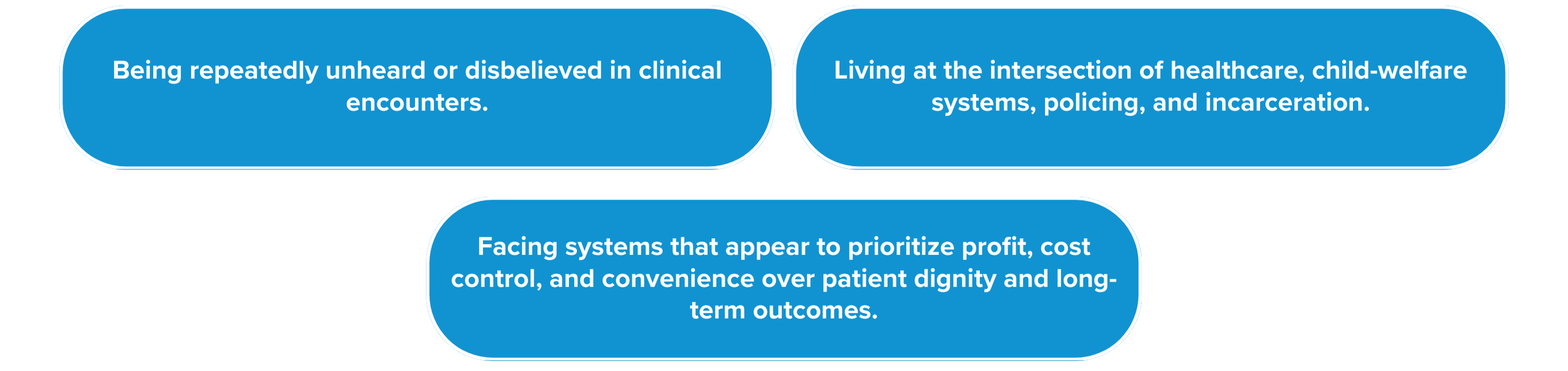

People described:

Terilyn Love captured the mood bluntly, noting that in the current environment “the only way to make people do right is to affect their pocketbooks,” underscoring how tightly trust and incentives are intertwined.

At the same time, the summit surfaced practical ways to rebuild trust. The group talked about the importance of stripping away jargon and meeting people “where they are,” both geographically and linguistically.

Marilee McGraw offered a phrase that many repeated throughout the day: “Research moves at the speed of trust.”

The idea was simple but profound: recruitment strategies, protocol designs, and operational timelines must be grounded in relationships—not the other way around.

Speakers pointed to community health workers, neighborhood-based hiring models, and long-term partnerships with community organizations as ways to show, not just say, that institutions intend to be present over time rather than parachuting in for a project and disappearing.

Mental health, trauma, and the biology of stress

Several sessions emphasized that mental and physical health are inseparable, especially in communities carrying the weight of discrimination, poverty, and violence. Panelist and Therapist Amy Shohet described work that stretches “from diapers to diapers” - supporting people from early childhood to older age.

At One Life Counseling Services, food pantries and other familiar community hubs are intentionally used as “front doors” to behavioral-health care. Families often arrive for groceries or basic support and are gradually introduced to mental-health services in a non-stigmatizing way.

Shohet shared research showing that child–parent psychotherapy can slow biological aging in both children and their caregivers. This is not just metaphor; it shows up in objective biological markers. In parallel, Pryor referenced the work of Dr. Hans Selye and others demonstrating that chronic stress is closely tied to organic disease. The group underscored that racism, homophobia, and other forms of discrimination are not just social problems—they create an ongoing stress load that literally wears down the body over time.

The shared conclusion was clear: you cannot meaningfully talk about cancer, HIV, Alzheimer’s, sickle cell disease, or any other chronic condition without accounting for mental health and trauma. Ignoring this is ethically incomplete and leads to worse outcomes and poor science.

Clinical-trial diversity: From compliance to scientific necessity

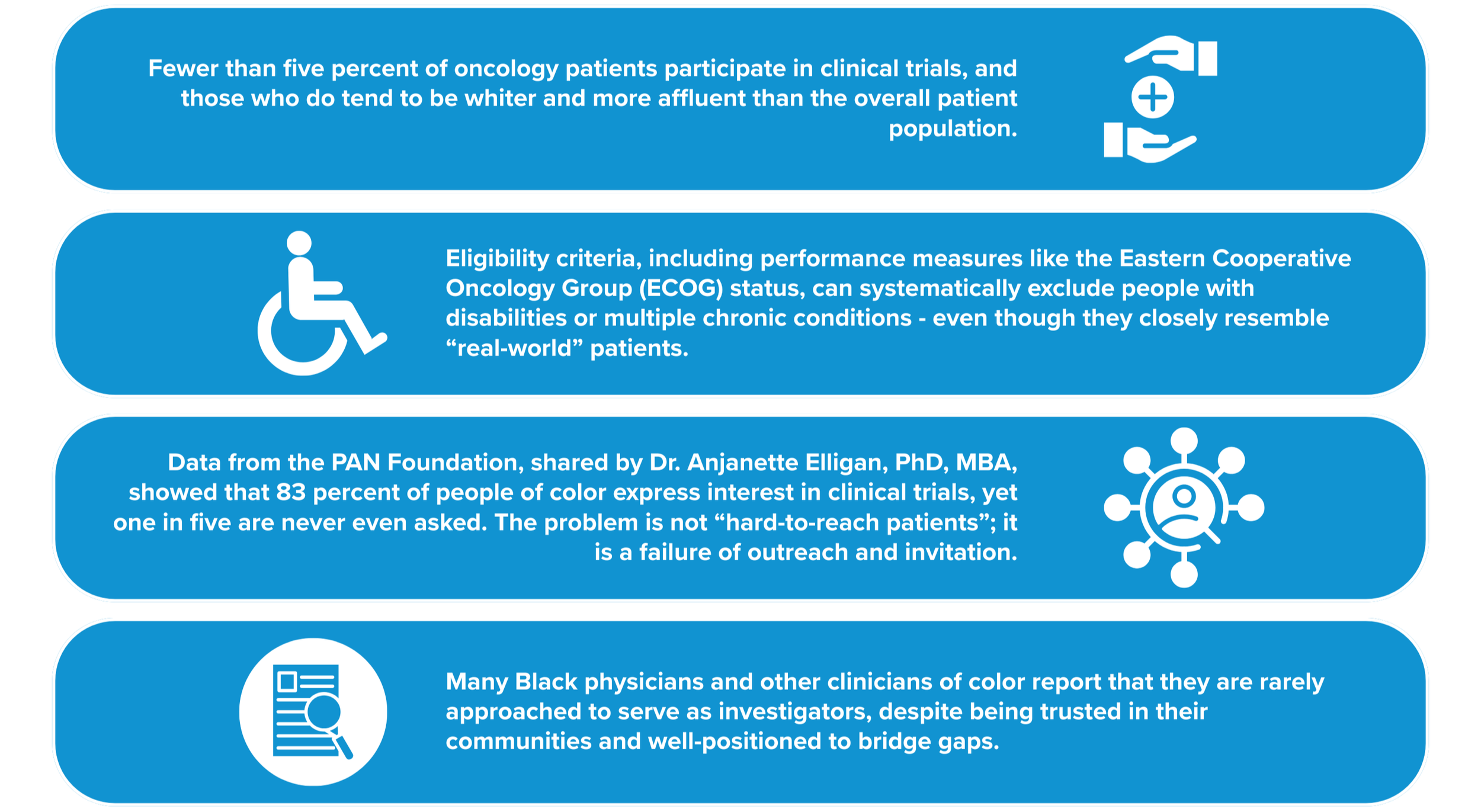

Ensuring diverse participation in clinical trials emerged as one of the most technically detailed and urgent themes.

Featured Speaker, Rochelle Williams-Belizaire emphasized that diversity in clinical research is not a branding or compliance issue; it is fundamental to scientific quality and safety.

Featured Speaker and BeOne Senior Vice President Melika Davis illustrated this point with stark examples. Early trials of warfarin, a commonly used blood thinner, substantially under-represented Black patients. When the drug moved into widespread use, dosing recommendations not grounded in genomic diversity led to systematic over-anticoagulation in Black patients. Similarly, the anti-seizure medication carbamazepine caused severe, sometimes life-threatening reactions in certain Asian populations because key genetic risk factors had not been captured in early studies.

These were not abstract anecdotes. They underscored that when trial populations do not reflect the people who will ultimately receive a drug, “harm is not hypothetical—it is predictable”.

Several barriers to inclusive trials were highlighted:

In response, BeOne Medicines described a set of deliberate structural choices in its clinical-operations model. In 2020, the company moved away from relying primarily on contract research organizations and transitioned to an in-house clinical operations model, with roughly 80 percent of work managed by internal staff and 20 percent by functional service providers. This shift has shortened trial start-up times, improved enrollment, and strengthened quality. Just as importantly, it has allowed BeOne to build deeper relationships with sites and communities, rather than treating them as interchangeable vendors.

Belizaire articulated BeOne’s philosophy as “solving with communities, not for them.” The company also reserves a share of trial participation for U.S. sites to help ensure that precision-oncology studies reflect domestic diversity, rather than being over-concentrated in a narrow set of international centers.

Speakers argued that precision oncology is increasingly reframing clinical trials as front-line treatment options, not a “last resort” once all other care has failed. That reframing has ethical implications: if trials can offer the most promising therapies, then excluding entire groups from those trials deepens inequity in both evidence and access.

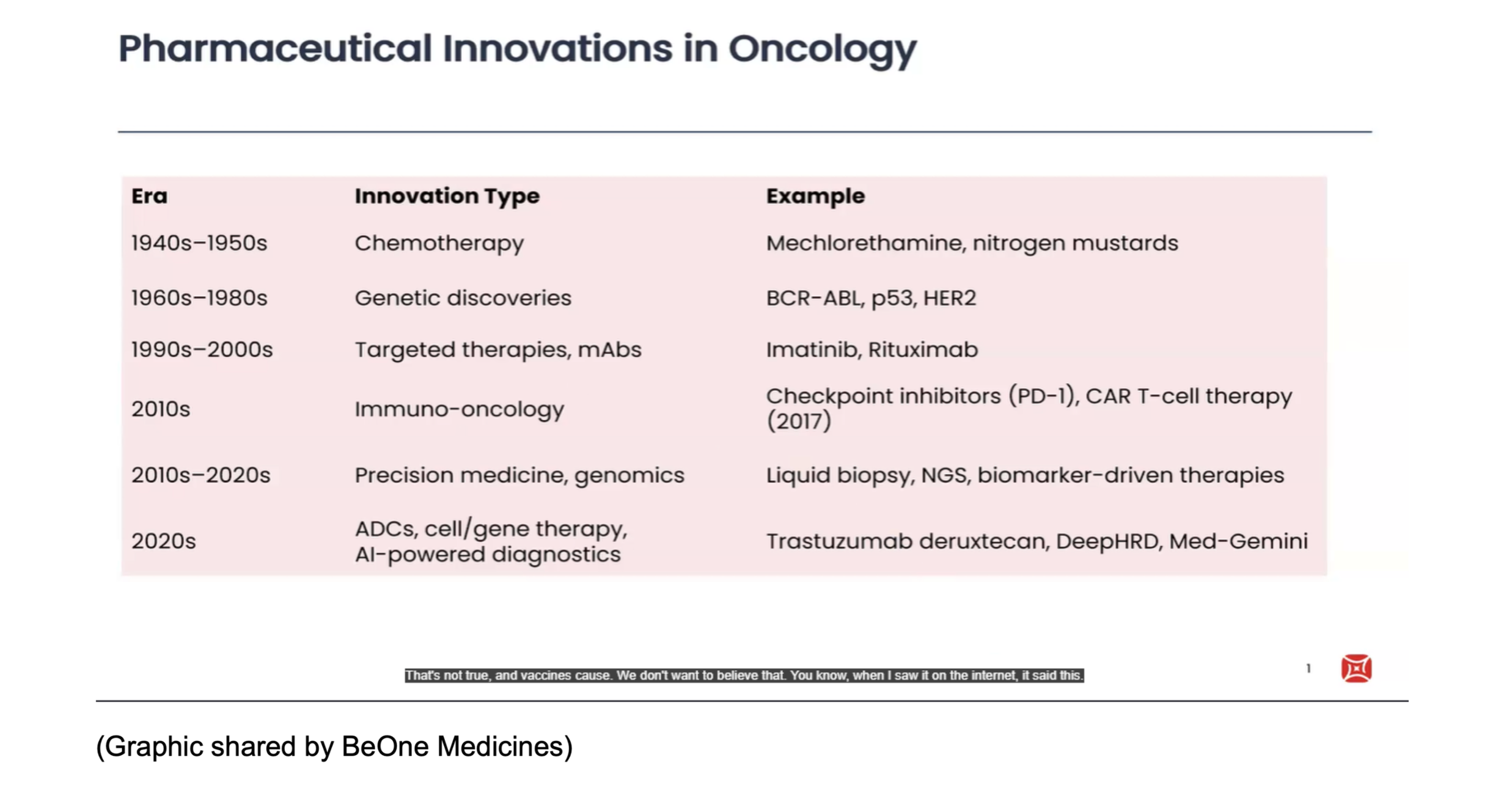

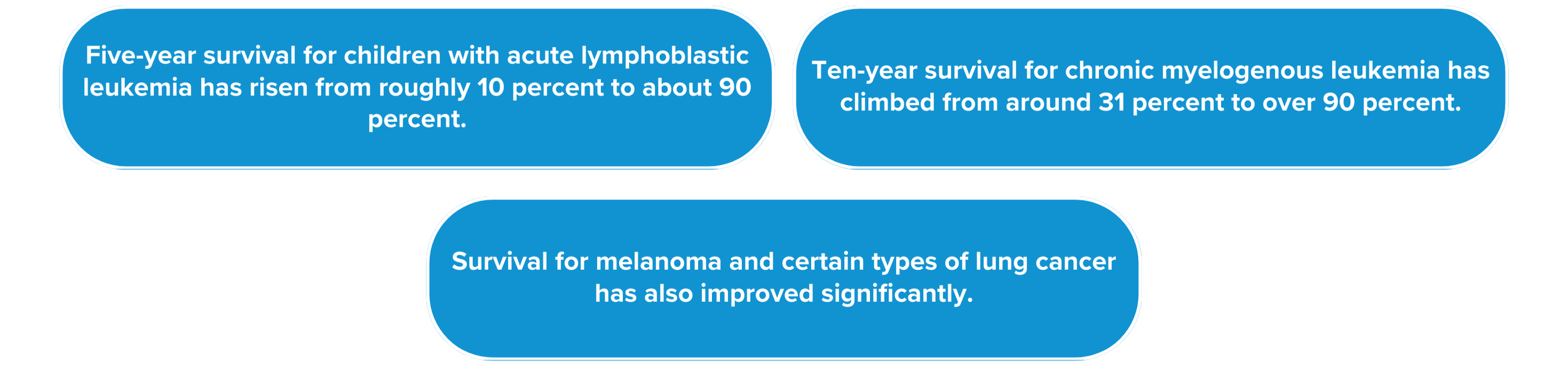

The impact of medical innovation and who benefits

Davis also presented a long view of oncology innovation, walking from the introduction of chemotherapy in the 1940s and 1950s through generations of targeted therapies and into the era of AI-powered diagnostics. Survival rates in several cancers have improved dramatically over the last seventy years.

For example:

None of this progress would have been possible without clinical trials. But as Pryor and others reminded the group, the benefits of these breakthroughs have not accrued evenly. When access to the best care depends on geography, insurance status, and social capital, innovation can actually widen disparities, even as average outcomes improve.

That tension—between progress in the aggregate and persistent gaps at the margins—ran through the entire day.

Technology and AI: Promise and peril

Technology and AI were discussed with both excitement and caution.

Global Head of DTC Innovation and Digital Health at BeOne Medicines, Anand Reddi described how major technology companies are moving aggressively into preventive care and behavior change. He spoke about “clickless search” and AI agents that people can simply talk to instead of typing queries, and he highlighted a perhaps surprising fact: older adults, including people in their seventies, eighties, and nineties, are deeply engaged with digital platforms and gaming. For those working in cancer and chronic disease, that means patients are not just in clinics—they are online, in game communities, and open to engagement there.

Others framed video games and live-streaming platforms as emerging preventive-health environments, where tailored messaging and community norms can influence behavior in subtle but powerful ways.

At the same time, participants voiced serious concerns. Pryor worried that predictive analytics could be used by insurers or employers to deny coverage, limit opportunities, or engage in a new form of algorithmic redlining. Love underscored that AI systems must be governed carefully because they can encode and amplify existing biases and can confidently “hallucinate” misinformation that looks authoritative.

Mental-health providers added another dimension: always-on digital tools can be tremendously helpful in expanding access to information and support—but they can also feed anxiety, compulsive use, and misinformation spirals.

Across disciplines, a consensus emerged: AI should augment, not replace, human clinicians and community workers. It should be developed and deployed within explicit ethical frameworks that prioritize equity from the outset. That includes designing systems with diverse data, regularly auditing for bias, and placing clear limits on how predictive health data can be used.

Policy, economics, and the structure of incentives

The summit also surfaced the ways that policy and economics shape what is possible on the ground.

Reddi used the global HIV response as a case study in how aligned incentives and coalitions can transform access. In 2003, roughly 50,000 people worldwide were on antiretroviral therapy. Through coordinated efforts across industry, governments, donors, and community advocates, that number has grown to well over 25 million. Pricing strategies, generics production, global funds, and persistent activism all contributed to that shift.

He noted that investing in HIV prevention and treatment in African-American communities in the U.S. South is not only the right thing to do morally—it is also economically advantageous, reducing downstream costs to the healthcare system.

Others, however, warned that current trends may be moving in the opposite direction. Participants described 2025 cuts to academic research and NIH-funded programs, as well as efforts to roll back diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Several shared personal stories of grants being cut and long-standing programs abruptly terminated, raising the fear that we could lose critical capacity just when it is most needed.

The implication was clear: if equity work depends on fragile, project-based funding and is not embedded in core incentives—reimbursement, quality metrics, regulatory expectations—it will remain vulnerable and uneven.

Health equity, the group concluded, must be written into the rules of the game, not left as a voluntary add-on.

Barriers and pain points: Why people can’t get to the care they need

Taken together, the day’s discussions painted a vivid picture of why so many people still struggle to connect with the healthcare and research opportunities they want.

These include:

Structural barriers: Under-resourced neighborhoods, lack of transportation, clinic locations far from where people live and work, network restrictions, and bureaucratic hurdles all make it harder to access specialty care and trials.

Information and navigation barriers: Clinical-trial language is complex; eligibility criteria feel opaque; people don’t know where to start or whom to trust. Providers may not have time or support to explain options in accessible ways.

Trust and relational barriers: Historical and ongoing harms, coupled with daily experiences of discrimination or dismissal, make many people understandably wary of participating in research or engaging with large institutions.

Psychological and social barriers: Trauma, chronic stress, depression, stigma, and social isolation can make it difficult to seek care consistently, follow through on referrals, or advocate within systems that feel hostile.

Policy and incentive barriers: When payment systems, productivity targets, and regulatory requirements reward speed and volume more than relationship-building and equity, even well-intentioned clinicians and organizations find it hard to act differently.

The summit did not pretend that these barriers can be swept away quickly. But it did generate concrete ideas for chipping away at them.

Solutions and emerging practices: What participants proposed

Throughout the day, speakers returned to several practical strategies that are already working in pockets and could be scaled.

1. Borrowing from the HIV and sickle-cell “playbooks.”

The global HIV movement showed how coalitions of activists, clinicians, policymakers, and industry can transform access through pricing strategies, policy reform, and community-driven messaging. New therapies for sickle cell disease are now testing our willingness to apply those same lessons in communities that have historically been neglected. Participants argued that oncology, sickle cell, Alzheimer’s disease, and other conditions need similarly coordinated approaches—especially for Black, Latino, Indigenous, and low-income communities.

2. Treating trials as care, not as a last resort.

By framing clinical trials as legitimate treatment options when they offer the best or most innovative care, clinicians can ethically and enthusiastically invite more patients—including those from marginalized groups—to participate. This requires clear communication, shared decision-making, and trial designs that do not automatically exclude people with comorbidities or disabilities.

3. Embedding care and research in communities.

From community health workers in the Philippines, Thailand, and South Africa to neighborhood-based models in Chicago, participants highlighted the power of bringing care where people already are: schools, food pantries, faith communities, LGBTQ+ centers, public-housing complexes. When care and research are locally rooted—and when staff are hired from the neighborhood—trust grows and navigation gets simpler.

4. Investing in neighborhood talent and local leadership.

Several organizations represented at the summit have intentionally hired staff from the communities they serve. This approach not only creates jobs; it builds a workforce that understands local realities and can translate between institutional expectations and community needs.

5. Designing AI and digital tools with equity in mind from day one.

Rather than bolting on fairness considerations at the end, the group urged that equity be a design requirement: from data collection and model training to user interfaces and consent processes. Community representatives should have a seat at the table when new tools are being conceived, not just when they are being rolled out.

6. Tying equity to dollars and accountability.

Finally, participants pointed to quality metrics, reimbursement structures, and regulatory frameworks as levers. If organizations are rewarded for expanding access, diversifying trial enrollment, and building long-term community partnerships—and penalized when they do not—behavior will change more quickly and sustainably.

Actionable next steps

By the end of the summit, a set of concrete next steps had emerged for BeOne Medicines, CHI, and their partners.

For BeOne Medicines, commitments included deepening community partnerships rather than relying solely on vendors; maintaining the in-house clinical-operations model and its 80/20 structure; keeping a dedicated portion of trial activity in the United States to sustain domestic representation; revisiting inclusion and exclusion criteria that unnecessarily screen out marginalized participants; recruiting more Black, Latino, and other under-represented physicians as investigators; and developing an internal ethics charter for the use of AI and advanced analytics in clinical research.

For CHI, the summit reinforced its role as a convener and catalyst. Next steps included codifying the “virtual boardroom” format as a repeatable model for bringing diverse stakeholders together; developing a health-equity position paper or white paper based on the summit’s insights; creating practical “Trust & Access” toolkits for clinicians; and establishing mechanisms to track and publicly report progress on key equity metrics over time.

Conclusion: From summit to sustained work

The BeOne Medicines & CHI West-Coast Summit on Health Equity made one thing unmistakably clear: health equity is both a moral imperative and a scientific necessity. We cannot claim to deliver the best possible care, or to develop the safest and most effective medicines, if entire communities remain under-served, under-studied, and under-represented.

Throughout the day, participants returned to a simple but demanding standard: solve with communities, not for them. That ethos requires humility, patience, and a willingness to change how power, resources, and expertise are shared. It also requires embedding equity in the structures—financial, regulatory, technological—that shape everyday decisions.

The summit was not framed as an endpoint, but as a starting point for deeper collaboration. The work ahead will involve policy and practice, science and storytelling, local experiments and global coalitions. But if the spirit of this gathering is carried forward, it offers a hopeful path: one in which future medical breakthroughs are not just impressive on paper, but genuinely accessible to everyone they are meant to serve.

Joseph Gaspero is the CEO and Co-Founder of CHI. He is a healthcare executive, strategist, and researcher. He co-founded CHI in 2009 to be an independent, objective, and interdisciplinary research and education institute for healthcare. Joseph leads CHI’s research and education initiatives focusing on including patient-driven healthcare, patient engagement, clinical trials, drug pricing, and other pressing healthcare issues. He sets and executes CHI’s strategy, devises marketing tactics, leads fundraising efforts, and manages CHI’s Management team. Joseph is passionate and committed to making healthcare and our world a better place. His leadership stems from a wide array of experiences, including founding and operating several non-profit and for-profit organizations, serving in the U.S. Air Force in support of 2 foreign wars, and deriving expertise from time spent in industries such as healthcare, financial services, and marketing. Joseph’s skills include strategy, management, entrepreneurship, healthcare, clinical trials, diversity & inclusion, life sciences, research, marketing, and finance. He has lived in six countries, traveled to over 30 more, and speaks 3 languages, all which help him view business strategy through the prism of a global, interconnected 21st century. Joseph has a B.S. in Finance from the University of Illinois at Chicago. When he’s not immersed in his work at CHI, he spends his time snowboarding backcountry, skydiving, mountain biking, volunteering, engaging in MMA, and rock climbing.